The Legal, Political, and Law-Enforcement Landscape Before Stonewall

In the years leading up to June 1969, LGBTQ+ New Yorkers navigated an oppressively hostile legal and political environment. Homosexuality was criminalized under various state and municipal laws, and gender-nonconforming individuals were specifically targeted by “three‑article” statutes—informal rules enforced by police that required anyone in public to wear at least three articles of clothing appropriate to their assigned sex at birth. Failing to meet this arbitrary standard could result in arrest for “impersonation” or “masquerading.” Such statutes were routinely used to raid bars, cafés, and private gatherings that catered to gay, lesbian, and transgender patrons, with undercover officers often entering establishments to document infractions before calling in backup for a formal bust.

The political climate of the 1950s and ’60s was shaped by McCarthy‑era purges and the broader “Lavender Scare,” in which federal and local governments systematically dismissed employees suspected of homosexuality. At the same time, New York City police viewed LGBTQ+ venues as morally suspect and frequently collaborated with state liquor authorities to revoke or deny licenses, justifying raids under the pretext of enforcing alcohol regulations. Many gay bars operated without official permits, making them especially vulnerable to closure and harassment.

| For an overview of how criminalization led to repeated bar raids and police brutality, see: LGBTQIA+ Studies Resource Guide on Stonewall Era Research Guides. |

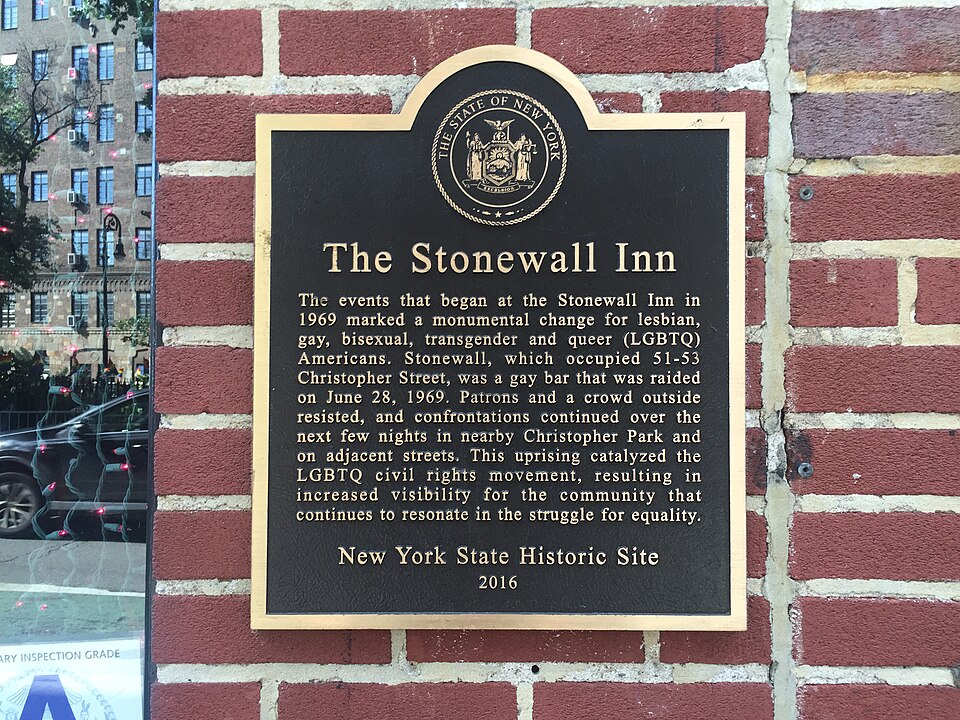

The Stonewall Raid and the Riots of June 28–July 3, 1969

Shortly after 1:20 a.m. on Saturday, June 28, 1969, the New York City Public Morals Squad executed one of its routine raids on the Stonewall Inn, a Mafia‑owned dive bar at 53 Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. Four undercover officers had spent the evening inside gathering evidence. Once they summoned backup, uniformed police burst in, turned off the jukebox, forced patrons to line up, and began inspecting IDs. Those perceived to be cross‑dressing were separated and—despite standard procedure—refused to submit to invasive strip searches.

As officers hauled away cases of beer and arrested nearly a dozen patrons for liquor and cross‑dressing violations, the usual pattern of compliance broke down. Bystanders—many of whom were gay, lesbian, drag queens, and homeless youth—refused to disperse. The confrontation began when a handcuffed woman fought back, and rumors that detainees were being beaten spread like wildfire. Shouts of “Gay power!” rang out as objects were hurled at police wagons. This spontaneous resistance ignited six nights of escalating demonstrations, becoming a turning point in resistance and collective, confrontational LGBTQ+ activism in U.S. history.

| A detailed account of the raid and its immediate aftermath is available on Wikipedia: Stonewall riots – Police raid section Wikipedia. For eyewitness narratives and scholarly analysis of those nights, see: The Stonewall Riots: Origins, Timeline & Leaders HISTORY. |

Christopher Street Liberation Day: The First Anniversary March

On Sunday, June 28, 1970—exactly one year after the initial uprising—organizers transformed grief and anger into a public demonstration. Dubbed Christopher Street Liberation Day, the march began at Washington Place and Sheridan Square, wound north along Sixth Avenue, and culminated in a “Gay‑In” at Central Park’s Sheep Meadow. What planners anticipated as a modest parade drew thousands of participants, both LGBTQ+ individuals and allies, declaring visibility and pride in the face of ongoing discrimination.

The success of Christopher Street Liberation Day inspired parallel actions in Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and beyond. By 1971, pride events had proliferated across U.S. cities and even crossed international borders to London, Paris, and Stockholm—transforming what began as a protest against police brutality into an annual celebration of LGBTQ+ identity, community, and resilience.

| For an expanded narrative on how Liberation Day evolved into “Pride,” see: Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day, The Story of the First Pride. |

These foundational events—the legal oppression of LGBTQ+ people, the Stonewall uprising, and the first anniversary march—laid the groundwork for Pride celebrations worldwide. In Lititz and beyond, Pride remains a testament to that legacy of resistance, visibility, and communal joy.

Donate Now to support our mission.

Check out the next article in this series: Why We Have Lititz Pride: From Hate to a Call to Choose Love